Suwon, Korea - February 2015

February 2015. I’m sitting in a restaurant in Suwon trying to figure out how to operate a Korean grill. The waitress shows me with gestures, so I follow along. Smoking meat on the table, small bowls of kimchi and other things I can’t name scattered around. The soju ran out a while ago.

This was classic Korean BBQ - those metal grills built into the table, smoke rising to the ceiling, meat sizzling on the grate. Something you can’t replicate outside Korea. It’s not just about taste - it’s the whole ritual, how you eat in a group, the banchan (those small side dishes) that appear without asking.

The restaurant was packed with locals - families, couples, groups of friends. Nobody spoke English. The menu was entirely in Korean with pictures that didn’t quite match what arrived at the table. But that’s the beauty of it. You point at something, hope for the best, and usually end up pleasantly surprised.

The banchan kept coming - little dishes of pickled radish, seasoned spinach, bean sprouts, various types of kimchi. Some were spicy enough to make your eyes water, others mild and almost sweet. The waitress would refill them without being asked, an endless parade of flavors. This is what I missed most after leaving Korea - not the main dishes, but these side dishes that transform every meal into an exploration.

Then came hot pot with glass noodles. In winter in Korea, it just makes sense - outside it’s 0°C, windy, and grey, and you’re sitting over a bubbling pot packed with vegetables and mushrooms.

The broth was rich and spicy, with that characteristic Korean heat that builds gradually rather than hitting you all at once. Glass noodles, mushrooms, vegetables, tofu - all swimming in this red-orange soup that warmed you from the inside out. Perfect for February, when Seoul’s winter cold seeps into your bones and refuses to leave.

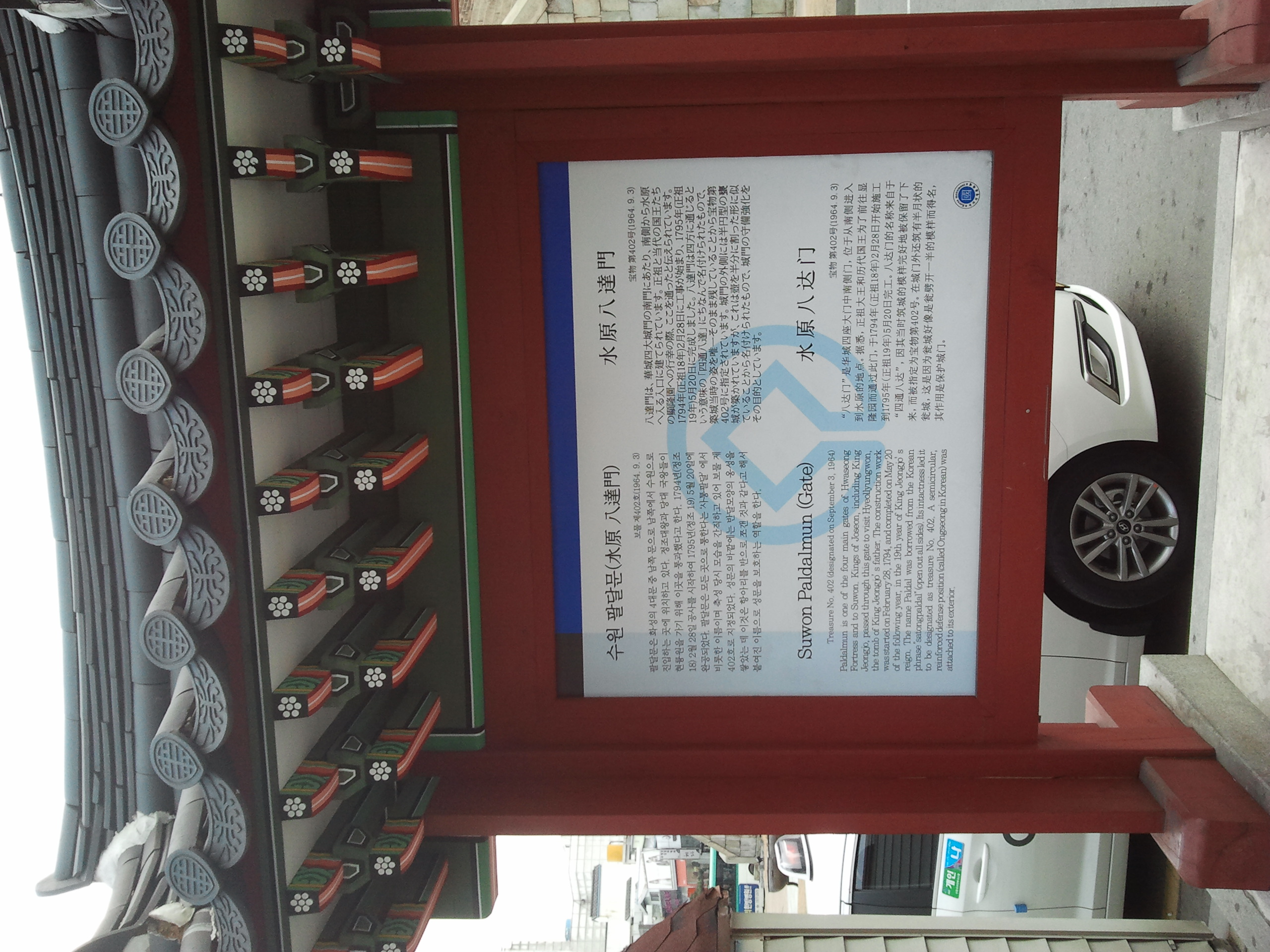

Hwaseong Fortress

Suwon sits about 30 km south of Seoul. Technically suburbs, but in practice a completely different city. Fewer tourists, less English, more authenticity. I came here mainly for Hwaseong Fortress - a UNESCO site from the 18th century that encircles the old town.

The journey there was typical Korean efficiency - subway from Seoul, perfectly timed connections, clear signage even if you can’t read Korean. The T-money card worked everywhere. Within 40 minutes, I was stepping out into a completely different world.

The fortress walls are massive. Stone blocks, watchtowers, gates with Chinese inscriptions. You can walk on the walls and get a panorama of the whole city - old roofs mixing with concrete blocks from the 70s, skyscrapers in the background.

Hwaseong Fortress was built between 1794 and 1796 under King Jeongjo. The walls stretch for 5.7 kilometers around the old city, featuring 48 structures including gates, bastions, observation towers, and command posts. What’s remarkable is how much survived - or was meticulously reconstructed after the Korean War.

Walking on top of the walls, you get a sense of scale. These weren’t decorative fortifications - they were serious military architecture. Arrow slits, strategic positions for defense, clever use of terrain. And yet there’s an aesthetic quality to them, the way the stone curves follow the natural contours of the land.

The contrast is what struck me most. Looking one direction, you see traditional Korean architecture - tile roofs, wooden structures, the kind of buildings that have existed for centuries. Turn your head, and there’s modern Suwon - apartment blocks, office buildings, the infrastructure of a contemporary Korean city. It’s not jarring though. Somehow Korea makes this juxtaposition work in a way that feels natural rather than dissonant.

I happened to catch some patriotic event at the fortress. Dozens of people in white shirts, everyone with Korean flags. I had no idea what was happening, but the energy was incredible.

It might have been related to the March 1st Independence Movement - Korea’s declaration of independence from Japanese colonial rule in 1919. Koreans take their patriotic celebrations seriously, with genuine emotion rather than performative nationalism. People sang, there were speeches in Korean I couldn’t understand, but the sentiment was clear. History matters here in a way that feels immediate, not distant.

There were street food stalls by the walls. I bought something on a stick - looked like fish, but I wasn’t sure. Taste? Weird, but good. One of those “just eat it and don’t ask” moments.

Korean street food is an adventure. Tteokbokki (spicy rice cakes), hotteok (sweet pancakes), odeng (fish cakes on sticks), sundae (blood sausage that’s nothing like the ice cream). Half the fun is not knowing exactly what you’re eating. The vendors are used to confused foreigners pointing and nodding. They’ll smile, hand you something, and you discover whether you’ve made a good choice or an interesting one.

The thing on a stick turned out to be some kind of seafood cake - processed fish formed into a tube, grilled until the outside was slightly crispy. Dipped in the sauce they provided, it was salty, slightly sweet, with that characteristic Korean spice that sneaks up on you. Not something I’d eat regularly, but perfect for a cold afternoon exploring ancient fortifications.

Chinese Garden

After the fortress, I went to the Chinese Garden. Korea has plenty of these - traditional Chinese architecture with pavilions, bridges, circular gates. February is the worst possible time - bare trees, brown grass, murky water in the ponds.

But there was something melancholic about it. Silence. Nobody around. Just me, cold wind, and these strange round gates (moongates) through which you could see concrete blocks from the 80s. The contrast was absurd - old China and new Korea in one frame.

Chinese gardens in Korea are reminders of the long historical relationship between the two countries - sometimes cooperative, sometimes confrontational, always influential. These gardens follow classical Chinese design principles: asymmetry, borrowed scenery, the interplay of water and stone, careful placement of pavilions to create specific views and moods.

In summer, these gardens would be lush - green bamboo, flowering plants, the ponds full and clear. In February, they’re stripped down to their essential architecture. You see the bones of the design, the structural elements that make these spaces work. The curved bridges, the carefully placed rocks, the pavilions positioned to frame specific views.

I spent maybe an hour just wandering. The cold kept me moving, but there was a meditative quality to it. Empty gardens have their own appeal - no crowds, no noise, just the sound of wind through bare branches and the occasional bird. The moongates - those circular openings in walls - create frames for views. You approach them, see what’s on the other side, step through into a different space. It’s theatrical, deliberate, and effective.

And then there were those moments where the frame captured something unintended - a concrete apartment building, a modern road, the infrastructure of contemporary Korea intruding on this carefully constructed historical fantasy. But that’s Korea. The old and new exist simultaneously, neither one dominating, both valid.

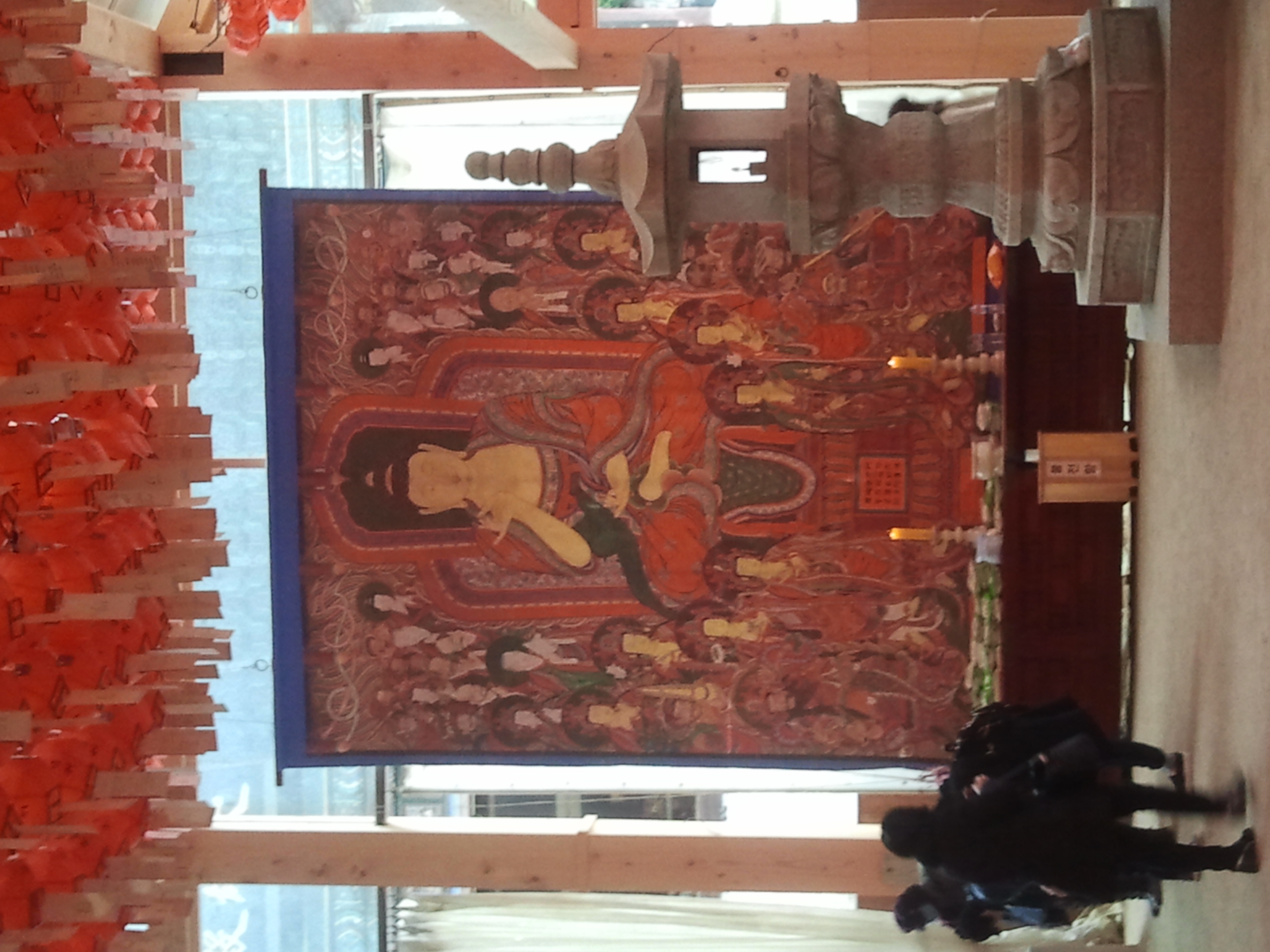

Buddhist Temples

Buddhist temples in Suwon are a separate topic. Those green-red roofs, colorful paintings, stone statues. Inside always the same atmosphere - incense smell, dim light, people praying quietly in the corner.

In one temple I saw a huge Buddha image - about 3 meters high, surrounded by hundreds of smaller figures. Red paper wishes hung from the ceiling. The atmosphere was surreal.

Korean Buddhist temples follow distinct architectural and decorative traditions. The colors - reds, greens, blues, oranges - are called “dancheong” and serve both aesthetic and protective functions. They’re not random; there’s symbolism in every color, every pattern, every placement.

You’re supposed to remove your shoes before entering the main hall. The floor is heated - ondol, traditional Korean underfloor heating. Even in February, stepping onto that warm floor from the cold outside is a small luxury. People were praying - not performative public prayer, but quiet, personal communication with whatever they were seeking. Some elderly women with their prayer beads, younger people bowing deeply, a few others just sitting in contemplation.

I’m not Buddhist, but there’s something universally calming about these spaces. Maybe it’s the incense, maybe the dim lighting, maybe just the accumulated energy of centuries of people coming here seeking peace or answers or just a moment of quiet. Whatever it is, it works.

Then I found a temple with a golden Buddha statue - maybe 10 meters tall. It stood on a hill, visible from the whole city. The halo was so intricate it looked like fractals.

The statue dominated the landscape - you could see it from various points around Suwon, this golden figure standing serenely above the urban sprawl. Up close, the craftsmanship was remarkable. The halo behind the Buddha was incredibly detailed, layers upon layers of decorative elements creating this mandala-like structure that seemed to shimmer in the gray February light.

There were other statues around the base - guardians, bodhisattvas, various figures from Buddhist cosmology. Each one carefully crafted, painted, positioned. The whole complex felt like a statement - Buddhism is alive in modern Korea, not just a historical relic but a living tradition.

The door paintings were another level of detail. Dragons, phoenixes, guardian spirits - all rendered in that distinctive Korean style that’s related to Chinese and Japanese temple art but distinctly different. There’s a boldness to Korean Buddhist art, a directness that appeals even to someone like me who barely understands the symbolism.

Shopping Mall

In the evening I ended up at a shopping mall. Korea does malls differently - they’re not just stores, they’re entire ecosystems. Food court with dozens of stalls on the ground floor, shops one level up, cinema higher, and on the top floor… an aquarium with jellyfish.

The jellyfish were lit by neons - pink, blue, purple. Hypnotic. I stood there for probably 20 minutes, watching them slowly swim. After a whole day walking on the cold fortress walls, there was something therapeutic about this warm, dark space with floating jellyfish.

Korean shopping malls are social spaces as much as commercial ones. Teenagers hanging out, families spending entire afternoons there, couples on dates. The aquarium wasn’t some massive Sea World-style attraction - just a dark room with tanks of jellyfish lit dramatically. But it worked. There’s something mesmerizing about jellyfish - the way they pulse through water, translucent and alien, indifferent to the humans watching them.

The lighting changed slowly - pink to blue to purple to green - creating different moods. Some jellyfish were tiny, barely visible. Others were substantial, their tentacles trailing behind them like silk ribbons. A few kids were there with their parents, pressing their faces against the glass. An elderly couple sat on a bench, just watching in silence.

On the first floor there was also a market with nuts and dried fruits - mountains of colorful products I didn’t recognize. Everything in open containers, smells mixing together.

This is where Korea’s food culture gets interesting. Dried fruits, nuts, seeds - some familiar (almonds, walnuts, dates), others completely foreign. Dried persimmons, candied ginger, things that might be seeds or might be dried fish eggs for all I could tell. The vendors would offer samples - tiny tastes on toothpicks. Some were sweet, some savory, some challengingly bitter or salty.

I bought a small bag of something that looked like dried plums. They turned out to be intensely sour, almost making my mouth pucker, with a slight sweetness underneath. Not what I expected, but interesting. That’s the theme of Korean food - interesting. Even when it’s not immediately delicious, it’s rarely boring.

Nightlife

At night Suwon transforms. The same streets that are normal during the day turn into a sea of neon in the evening. Everything glows - restaurants, karaoke bars, PC bangs (computer cafes), convenience stores.

The neon transformation happens gradually as the sun sets. First a few signs light up, then more, then suddenly the entire street is glowing. It’s not subtle - this is Korea, where more is always better when it comes to lighting. Every business competes for attention with brighter, bigger, more colorful signs.

Korean neon signs are a separate language. They’re not subtle like in Japan, they’re loud, colorful, screaming. They compete for attention. And it works - the streets are full of people even at midnight.

The streets were busy - people heading to restaurants for late dinners, groups of friends going to noraebang (karaoke rooms), students heading to PC bangs for marathon gaming sessions. Korean nightlife isn’t about clubs and bars the way it is in Western cities. It’s more about food, socializing in groups, activities.

I grabbed something from a convenience store - one of those triangle kimbap packages, an iced coffee, some snacks I couldn’t identify from the packaging. Korean convenience stores are remarkable - clean, well-stocked, open 24/7, and they have everything. Need socks? They have socks. Want instant ramyeon? Twenty varieties to choose from. Looking for a phone charger? Multiple options.

The iced coffee was sweet - Koreans like their coffee sweet - but good after a day of walking. I sat on a bench outside, eating my kimbap, watching people pass. Nobody paid attention to the foreign guy sitting there - Korea’s big cities are cosmopolitan enough that foreigners don’t draw stares anymore.

Return

A few days later, Incheon Airport. Korean Air waiting at the gate - those characteristic blue planes with the taegeuk logo. The trip is ending.

Incheon Airport is consistently rated one of the best airports in the world, and it shows. Clean, efficient, logical layout, fast WiFi, comfortable seating. But I wasn’t thinking about airport ratings. I was thinking about the past few days - the food I’d eaten, the places I’d seen, the small interactions that don’t make it into photos but stick in memory anyway.

The old woman who helped me find the right subway line even though we shared no common language, using gestures and patience. The restaurant owner who gave us extra banchan without charging. The teenager who complimented my shoes in broken English, proud to practice his language skills. The small moments that make travel memorable.

Suwon isn’t in the top 10 places to see in Korea. Nobody flies to Korea “to see Suwon.” But that’s exactly why it was worth it. There were no hordes of tourists taking the same photos in the same places. There was authenticity - people living normal lives, not posing for Instagram.

Major tourist destinations have their place - there’s a reason millions of people visit Gyeongbokgung Palace or Jeju Island. But there’s value in going to the places that don’t make the highlight reels, the cities where tourism is a side note rather than the main economy. That’s where you find authentic experiences, where restaurants serve locals rather than tourists, where you’re more likely to have conversations and small adventures.

Hwaseong Fortress was impressive. Temples - peaceful. Chinese Garden - melancholic. Street food - weird but good. Neon signs - hypnotic.

Would I go back? Probably yes, but in a different season. Spring or fall. See those gardens when they’re not dead. But on the other hand - the winter emptiness had its charm. No crowds. It was raw, cold, authentic.

February in Korea means cold weather, fewer tourists, gray skies. But it also means lower prices, empty attractions, the country without its makeup on. You see it as it actually is, not the polished version presented during peak season. There’s honesty in that.

Korea in February 2015. I remember the cold. I remember the food. I remember the contrast between ancient walls and modern buildings, between traditional temples and neon-lit streets. I remember feeling like a visitor but also feeling welcome, like Korea didn’t mind sharing itself with someone willing to wander off the beaten path.

The flight home was long, comfortable, unremarkable. Korean Air does service well - attentive but not intrusive, good food, clean planes. But I wasn’t thinking about the flight. I was already planning the next trip, wondering what else Korea had to show me, what other cities existed beyond Seoul and Busan, what other stories were waiting to be discovered.

Korea in February 2015. I remember.