Networking Lab Session: From Theory to Practice - A Detailed Report

This post documents my hands-on experience with computer networking lab sessions, where theoretical knowledge transformed into practical skills. From configuring Cisco routers to troubleshooting complex network topologies, this session bridged the gap between classroom learning and real-world network engineering.

Lab Duration: Full session completed. Equipment: Cisco 2500 series routers, switches, multi-device topology. Skills Gained: CLI configuration, routing protocols, network troubleshooting.

The Equipment: Real Hardware, Real Learning

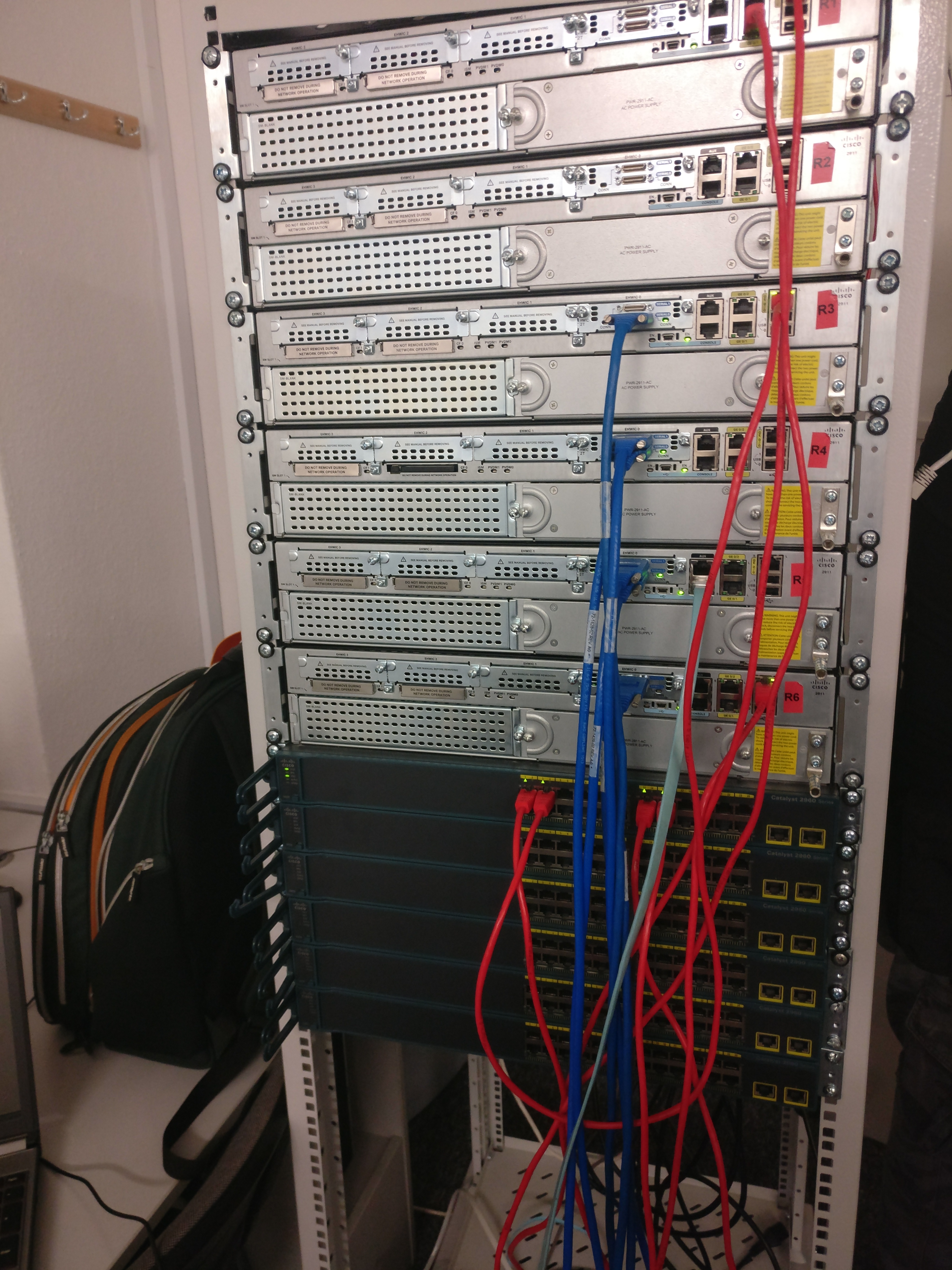

Walking into the networking lab for the first time, I was immediately struck by the impressive rack of equipment towering in the corner of the room. This wasn’t a simulation on a laptop screen or a virtual environment running in the cloud - these were real, physical devices with blinking lights, humming fans, and the unmistakable presence of actual network infrastructure. The weight of knowing I’d be working with equipment used in production environments worldwide added both excitement and a touch of nervousness to the experience.

The centerpiece of our laboratory was an impressive rack housing multiple networking devices, each playing a crucial role in our learning topology. Unlike working with software simulations where you can simply click “reset” if something goes wrong, this hardware demanded careful attention and methodical approaches. Every cable connection mattered, every configuration command had real consequences, and troubleshooting required systematic thinking rather than random trial and error.

Cisco 2500 Series Routers: The Legendary Workhorses

Our primary devices were Cisco 2500 series routers - equipment that has earned legendary status in the networking world. While these routers aren’t the newest models on the market, they remain exceptional teaching tools precisely because they expose students to fundamental networking concepts without the abstraction layers that modern devices sometimes add. Working with these routers meant understanding networking at its core, without shortcuts or simplified interfaces to hide the complexity beneath.

Each router featured multiple types of interfaces that taught us about different network connection scenarios. The serial interfaces allowed us to simulate WAN connections between distant sites, giving us hands-on experience with protocols and configurations used in real wide-area networks. The Ethernet ports provided LAN connectivity, letting us build local networks and understand how routers segment and connect different network segments. Perhaps most importantly, the console ports gave us direct configuration access, teaching us the critical skill of working with command-line interfaces that remain the foundation of network administration.

These routers supported multiple routing protocols including RIP (Routing Information Protocol), OSPF (Open Shortest Path First), and EIGRP (Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol). This variety wasn’t just academic - it gave us the opportunity to understand how different routing protocols approach the same fundamental problem of finding paths through networks, and to appreciate why network engineers choose specific protocols for specific scenarios.

Each router in our lab was carefully labeled with clear designations like R3, R4, and R5. This seemingly simple organizational choice proved invaluable during our work. When troubleshooting a connectivity problem or verifying a routing configuration, being able to quickly identify which physical device corresponded to which logical component of our network topology saved countless hours and prevented numerous configuration mistakes.

The Rainbow of Cables: Organization in Color

One of the most visually striking aspects of the lab rack was the colorful array of cables connecting various devices. To the untrained eye, it might have looked like chaos - a tangle of colored wires running in multiple directions. However, this “chaos” was actually a sophisticated organizational system that professional network engineers use to maintain clarity in complex installations.

The blue cables formed the backbone of our standard Ethernet connections, linking switches to routers and creating the data paths that would carry our network traffic. These weren’t randomly chosen blue cables - in networking conventions, blue often indicates standard patch cables, and seeing blue instantly told us we were looking at regular network connections rather than specialized links.

Red cables in our topology marked critical or special-purpose connections. In production environments, red cabling might indicate connections that should never be accidentally disconnected, or links that carry particularly important traffic. During our lab sessions, red cables helped us quickly identify key connections when troubleshooting, allowing us to prioritize checking these paths when investigating connectivity issues.

The green cables served a specialized purpose - these were our console cables, the physical connections that gave us direct administrative access to device configuration interfaces. Console connections are unique in networking because they work independently of the network itself. Even if we completely misconfigured a router’s network settings and lost all network connectivity, the green console cable still provided a reliable path to fix the problem. This taught us an important lesson about out-of-band management and the importance of always maintaining alternative access methods to critical infrastructure.

White and gray cables rounded out our color scheme, typically serving as additional network connections or in some cases indicating different types of traffic flows. The key lesson wasn’t memorizing which color meant what - it was understanding that color coding in cable management isn’t arbitrary decoration, it’s a critical organizational tool that makes the difference between efficient troubleshooting and spending hours tracing individual cables through a tangled mess.

This color coding proved its value repeatedly during our troubleshooting sessions. When trying to verify if two devices were properly connected, a quick visual scan of cable colors could immediately confirm whether we were looking at the right connection type. When tracing a network path to understand how traffic flowed through our topology, following the cable colors provided visual breadcrumbs that made the invisible network paths visible and understandable.

Configuration Workflow: From Console to Connectivity

The process of transforming a powered-off router into a functioning network device required methodical progression through several configuration stages. Each stage built upon the previous one, and skipping steps or rushing through configurations invariably led to problems that took longer to fix than doing it right the first time would have taken.

Step 1: Establishing Initial Access and Basic Configuration

Our journey into router configuration began with the most fundamental step - physically connecting to the device. Using a console cable (technically called a rollover cable because of how its internal wires are arranged), we established a direct connection between a laptop’s serial port and the router’s console port. This connection was independent of any network configuration, giving us reliable access even to a completely unconfigured device.

We used terminal emulation programs like PuTTY or SecureCRT to communicate with the router through this console connection. These programs create a text-based interface to the router’s operating system - Cisco IOS (Internetwork Operating System). The first time you successfully connect and see the router’s prompt appear on your screen is a genuinely exciting moment. That simple “Router>” prompt represents the gateway to configuring every aspect of how this device will function in a network.

The Cisco IOS command-line interface operates through a hierarchical system of modes, each with different capabilities and purposes. Understanding these modes and how to navigate between them is fundamental to effective router configuration. We began in user EXEC mode, indicated by the “>” prompt, which offers limited monitoring capabilities. Entering the enable command elevated us to privileged EXEC mode, shown by a “#” prompt, where we could view (but not change) complete configuration details.

To actually configure the router, we needed to enter global configuration mode using the configure terminal command. From there, we could set the router’s hostname, making it easier to identify which device we were working on:

Router> enable

Router# configure terminal

Router(config)# hostname R3

R3(config)#

Notice how the prompt changed at each step, providing constant feedback about our current position in the command hierarchy. This seemingly small detail becomes crucial when managing multiple devices or executing complex configuration sequences - you always know exactly where you are and what commands are available.

Security configuration came next. In production environments, routers often contain or control access to sensitive systems, so proper password protection is non-negotiable. We configured several types of passwords, each serving a different purpose:

The enable secret password protects access to privileged EXEC mode, preventing unauthorized users from viewing or changing critical configurations. Console passwords protect the physical console port - important in environments where someone might gain physical access to equipment. VTY (Virtual TeleType) passwords protect remote access via Telnet or SSH, the methods administrators use to manage routers from other locations.

R3(config)# enable secret mySecretPassword

R3(config)# line console 0

R3(config-line)# password myConsolePassword

R3(config-line)# login

R3(config-line)# exit

R3(config)# line vty 0 4

R3(config-line)# password myVTYPassword

R3(config-line)# login

R3(config-line)# exit

We also configured banner messages - the text that appears when someone connects to the router. While this might seem purely cosmetic, banners serve important legal and practical purposes. They can display legal warnings about unauthorized access, provide contact information for authorized users, or display network status information.

The next critical step was configuring network interfaces with IP addresses. A router without IP addresses is like a post office with no address - it can’t send or receive anything because it has no identity on the network. Each interface needed an IP address appropriate for its position in the network topology:

R3(config)# interface FastEthernet0/0

R3(config-if)# ip address 192.168.1.1 255.255.255.0

R3(config-if)# description Connection to LAN Segment A

R3(config-if)# no shutdown

R3(config-if)# exit

The no shutdown command deserves special attention because forgetting it is one of the most common mistakes beginners make (and experienced engineers still occasionally make in moments of distraction). Cisco router interfaces default to an administratively down state - they’re deliberately turned off. You must explicitly enable them with no shutdown. The rationale behind this default behavior is safety - it prevents accidentally disrupting network traffic when adding new equipment. However, it also means your carefully configured interface won’t work until you remember this crucial command.

The description command, while optional, proved incredibly valuable. When troubleshooting or reviewing configurations weeks later, these descriptions provided instant context about each interface’s purpose. “FastEthernet0/0” is just a technical designation, but “Connection to LAN Segment A” immediately tells you what that interface does and why it matters.

Step 2: Building the Physical Network Topology

With basic router configurations complete, we moved to the fascinating task of physically connecting devices to create our network topology. This is where theory literally becomes tangible - you’re not drawing network diagrams on paper or arranging icons in simulation software, you’re holding actual cables and connecting real equipment.

The first challenge was understanding the topology we needed to build. Our instructor provided network diagrams showing how routers should interconnect, which interfaces should connect to which, and what types of connections each link represented. Translating these logical diagrams into physical cable connections required careful attention and systematic approach.

We learned to identify which ports on which devices needed to communicate. This wasn’t always straightforward - a diagram showing R3 connected to R4 didn’t tell us whether to use FastEthernet0/0 or FastEthernet0/1, or whether this should be a serial connection or an Ethernet connection. These decisions required understanding both the logical requirements of our network design and the physical capabilities of our equipment.

Selecting appropriate cable types proved more complex than expected. Networking uses several cable types, each designed for specific connection scenarios. Straight-through cables connect unlike devices (router to switch, computer to switch), while crossover cables connect similar devices (router to router, switch to switch - though many modern devices auto-detect and adjust). Serial cables connect routers across WAN links. Choosing the wrong cable type results in connections that physically exist but logically don’t work.

The physical act of connecting cables required more care than I initially expected. Network ports can be damaged by forcing connectors at wrong angles or by not fully seating connections. We learned to listen for the click of an RJ-45 connector fully seating, to verify that serial cable screws were finger-tight but not over-tightened, and to route cables neatly to avoid accidental disconnections.

Verification came through multiple signals. Most network interfaces have LED indicators that light up when connections are properly established. On routers and switches, these LEDs provide immediate feedback about physical connectivity - if the light doesn’t come on, something’s wrong with the physical connection before you even begin troubleshooting logical issues. We learned to trust these indicators and to check them first when connections didn’t work as expected.

Building the topology also taught us about cable management - a skill that seems mundane but proves critical in real environments. Cables needed to be long enough to reach between devices without tension (which could pull connections loose), but not so long that excess cable created tangled messes. We learned to route cables along rack edges, to use cable ties (loosely - never tight enough to damage cables), and to label connections when topologies grew complex.

Step 3: Configuring Routing Protocols

With routers configured and physically connected, we faced the central challenge of networking - making them intelligently forward traffic between networks. This is where routing protocols come in, and where much of a network engineer’s expertise lies.

We began with static routing, the most straightforward approach where we manually tell each router how to reach each network. Static routing gave us complete control and deep understanding of routing fundamentals:

R3(config)# ip route 192.168.2.0 255.255.255.0 10.0.0.2

R3(config)# ip route 192.168.3.0 255.255.255.0 10.0.0.6

Each static route command explicitly tells the router: “To reach network 192.168.2.0/24, send packets to the next-hop router at 10.0.0.2.” This approach works well in small, stable networks, but has significant limitations. Every new network requires manual configuration on every router that needs to reach it. If network topology changes, administrators must manually update routes. In a network with dozens or hundreds of routers, static routing becomes unmaintainable.

This limitation led us to dynamic routing protocols, which allow routers to automatically share routing information and adapt to topology changes. We implemented RIP (Routing Information Protocol), one of the oldest and simplest dynamic protocols:

R3(config)# router rip

R3(config-router)# version 2

R3(config-router)# network 192.168.1.0

R3(config-router)# network 10.0.0.0

R3(config-router)# no auto-summary

With RIP configured, something almost magical happened. Without any additional configuration on our part, routers began exchanging routing information, building complete pictures of network topology, and automatically calculating best paths to all destinations. We could view this happening in real-time using debug commands, watching as routers sent updates every 30 seconds, learned about distant networks from neighbors, and adjusted routing tables as we added or removed connections.

RIP taught us fundamental concepts like metric (how protocols measure path quality), convergence (how long protocols take to adapt to changes), and the difference between classful and classless routing. However, it also showed us RIP’s limitations - its maximum hop count of 15 makes it unsuitable for large networks, and its 30-second update interval means slow convergence when topology changes.

These limitations naturally led to discussions about more advanced protocols like OSPF (Open Shortest Path First), which uses link-state algorithms for faster convergence and better scaling, or EIGRP (Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol), Cisco’s proprietary protocol combining advantages of distance-vector and link-state approaches. While we only touched on these briefly, understanding why different protocols exist and when to use each one gave us appreciation for the complexity and sophistication of modern networks.

Step 4: Testing, Verification, and the Art of Troubleshooting

Configuration without verification is hope, not engineering. The final crucial step in our workflow was systematically testing our network and verifying that configurations achieved their intended purposes. This is where we learned that networking isn’t just about configuring devices - it’s about developing the analytical mindset to prove configurations work correctly and to diagnose problems when they don’t.

Our primary testing tool was ping, the networking equivalent of “are you there?” When you ping an IP address, your device sends special packets called ICMP echo requests, and the destination (if reachable and properly configured) responds with ICMP echo replies:

R3# ping 192.168.2.1

Type escape sequence to abort.

Sending 5, 100-byte ICMP Echos to 192.168.2.1, timeout is 2 seconds:

!!!!!

Success rate is 100 percent (5/5), round-trip min/avg/max = 1/2/4 ms

Those five exclamation marks represent five successful replies - confirmation that our configuration works. But ping results aren’t always this clean. Sometimes you see periods (indicating timeouts), or a mix of exclamation marks and periods (indicating intermittent connectivity). Each pattern tells a story about what’s working and what’s not.

Traceroute took our testing to the next level by showing not just whether we could reach a destination, but the complete path packets took to get there:

R3# traceroute 192.168.3.1

Type escape sequence to abort.

Tracing the route to 192.168.3.1

1 10.0.0.2 4 msec 4 msec 4 msec

2 10.0.0.6 8 msec 8 msec 8 msec

3 192.168.3.1 12 msec 12 msec 12 msec

This output reveals that packets from R3 to 192.168.3.1 traverse three hops, passing through intermediate routers at 10.0.0.2 and 10.0.0.6 before reaching the destination. This information proved invaluable when troubleshooting - if packets weren’t reaching their destination, traceroute showed exactly where they stopped, pointing us directly to the problem location.

Show commands became our windows into router operation, revealing the internal state that determined how devices behaved. The show ip route command displayed routing tables - the databases routers use to make forwarding decisions:

R3# show ip route

Codes: C - connected, S - static, R - RIP, M - mobile, B - BGP

D - EIGRP, EX - EIGRP external, O - OSPF, IA - OSPF inter area

Gateway of last resort is not set

10.0.0.0/30 is subnetted, 2 subnets

C 10.0.0.0 is directly connected, Serial0/0

C 10.0.0.4 is directly connected, Serial0/1

C 192.168.1.0/24 is directly connected, FastEthernet0/0

R 192.168.2.0/24 [120/1] via 10.0.0.2, 00:00:15, Serial0/0

R 192.168.3.0/24 [120/2] via 10.0.0.2, 00:00:15, Serial0/0

This output contains a wealth of information. The “C” codes indicate directly connected networks - networks with interfaces on this router. The “R” codes show routes learned via RIP. The numbers in brackets [120/1] indicate administrative distance (120) and metric (1). Each line tells us not just where networks are, but how the router learned about them and how it makes forwarding decisions.

The show ip interface brief command provided quick status overviews of all interfaces:

R3# show ip interface brief

Interface IP-Address OK? Method Status Protocol

FastEthernet0/0 192.168.1.1 YES manual up up

FastEthernet0/1 unassigned YES unset administratively down down

Serial0/0 10.0.0.1 YES manual up up

Serial0/1 10.0.0.5 YES manual up up

This single command revealed interface IP addresses, whether interfaces were configured (OK?), how configurations were applied (manual vs DHCP), physical status (up/down), and protocol status (whether layer 2 and layer 3 were operational). When troubleshooting, this command instantly revealed if interfaces were down, misconfigured, or had conflicting addresses.

The show running-config command displayed complete current configurations - every setting on the router. This command became essential for verifying configurations matched our intentions, for documenting network configurations, and for comparing configurations between devices to identify discrepancies:

R3# show running-config

Building configuration...

Current configuration : 1450 bytes

!

version 12.4

!

hostname R3

!

enable secret 5 $1$mERr$hx5rVt7rPNoS4wqbXKX7m0

!

interface FastEthernet0/0

ip address 192.168.1.1 255.255.255.0

description Connection to LAN Segment A

!

router rip

version 2

network 192.168.1.0

network 10.0.0.0

no auto-summary

!

end

Finally, show protocols gave us a quick overview of interface and routing protocol statuses, perfect for rapid assessment of overall network health.

These verification commands weren’t just testing tools - they were diagnostic instruments that guided our troubleshooting process. When something didn’t work, we didn’t randomly change configurations hoping to fix it. Instead, we systematically gathered information using show commands, formed hypotheses about the problem, tested those hypotheses, and only made changes when we understood what was wrong and how to fix it.

Theory vs Practice: Where Reality Diverges from Expectations

The gap between understanding networking concepts theoretically and implementing them practically is far wider than most students expect. Reading about protocols in textbooks or watching configuration demonstrations provides valuable knowledge, but it fundamentally differs from wrestling with actual equipment that behaves in unexpected ways, produces cryptic error messages, and demands deep understanding to coax into cooperation.

Problem 1: “According to Theory This Should Work, But Reality Disagrees”

Perhaps the most frustrating and educational situations arose when our configurations perfectly matched documented procedures, looked entirely correct, but simply didn’t work. These moments forced us beyond rote memorization into genuine understanding.

One common culprit was the administratively down interface state. After carefully configuring an interface with the correct IP address and subnet mask, verifying our entries multiple times, we’d test connectivity only to find complete failure. Checking interface status revealed the problem - despite our careful configuration, the interface was “administratively down.” We’d forgotten the no shutdown command, that seemingly tiny detail that makes the difference between configured and operational.

This mistake taught us that Cisco’s design philosophy prioritizes safety over convenience. Interfaces default to shutdown specifically to prevent accidental network disruption. When adding equipment to production networks, having interfaces automatically activate could inadvertently create routing loops, bridging loops, or other catastrophic conditions. The no shutdown requirement forces deliberate activation, ensuring administrators consciously choose to enable interfaces. In practice, this means network engineers develop habits of always including no shutdown in interface configurations, making this deliberate choice automatic through discipline rather than default behavior.

Subnet mask miscalculations produced particularly insidious problems. Consider two interfaces that should communicate: one configured as 192.168.1.1/24 and another as 192.168.1.2/25. To someone learning networking, these look reasonable - they’re both in the 192.168.1.0 range, right? Wrong. The first address is in network 192.168.1.0/24 (addresses 192.168.1.0-192.168.1.255), while the second is in network 192.168.1.0/25 (addresses 192.168.1.0-192.168.1.127). These devices are in different logical networks despite appearing to be neighbors, and they won’t communicate directly. No amount of troubleshooting routing will fix a problem at the IP addressing layer.

Missing return routes created another category of problems that confused beginners. We’d configure R3 with a route to reach R5’s network, successfully ping from R3 to R5, then grow perplexed when R5 couldn’t ping back to R3. The problem was asymmetric routing information - R3 knew how to reach R5, but R5 didn’t know how to return traffic to R3. Packets successfully reached their destination but replies got lost because the return path didn’t exist. This taught us that routing must work bidirectionally - for two-way communication, both directions need complete routing information.

Protocol mismatches manifested in subtle ways. Perhaps R3 was running RIPv2 while R4 ran RIPv1. They might partially work, occasionally exchanging routes, but inconsistently. Or one router might be running RIP while its neighbor ran OSPF - they’d never exchange routing information because they weren’t speaking the same language. These problems reinforced that routing protocols must match across topology, and that careful documentation of protocol choices prevents painful debugging sessions.

Physical layer problems reminded us that networking isn’t purely logical - it exists in the physical world with all its messiness. Loose cables, damaged ports, wrong cable types, incorrect pinouts - these physical problems manifested as logical symptoms that could mislead troubleshooting efforts. We learned the golden rule: when troubleshooting, always verify physical connectivity first. No amount of sophisticated protocol analysis helps if the cable is unplugged.

Problem 2: Mastering the Nuances of CLI Syntax

The Cisco IOS command-line interface initially appears straightforward - you type commands, the router executes them. However, this simplicity conceals substantial complexity in its hierarchical mode structure and context-sensitive command availability.

Understanding when to use privileged EXEC mode (enable) versus global configuration mode (configure terminal) versus specific configuration modes (interface configuration, router configuration, line configuration) required developing an internal mental model of the command hierarchy. Beginners often attempted commands in wrong modes - trying to configure an interface while in global configuration mode, or attempting global configuration commands while in interface configuration mode. The CLI would respond with error messages, but these errors weren’t always clear about the real problem.

The context sensitivity of commands created additional complexity. Some commands exist in multiple modes with different meanings or options depending on context. The ip address command works in interface configuration mode to set interface addresses, but not in global configuration mode. The show commands work in privileged EXEC mode but not in configuration modes. Learning which commands worked where, and how to navigate efficiently between modes, required practice and often frustration.

Fortunately, Cisco IOS includes excellent built-in help through the question mark (?) feature. Typing ? at any prompt shows available commands. Typing partial commands followed by ? shows completion options. Typing commands followed by ? shows required or optional parameters. This help system became invaluable for exploration and learning, allowing us to discover commands and options without constantly consulting reference documentation.

Tab completion provided another helpful feature - typing partial commands and pressing tab would complete them if unambiguous, or show options if multiple matches existed. These small interface conveniences significantly improved efficiency once we learned to use them reflexively.

Problem 3: Understanding That Configuration Order Creates Critical Consequences

One of the more subtle lessons involved recognizing that in networking, the sequence of operations often matters as much as the operations themselves. This contrasts with many other computing contexts where operations are stateless or order-independent.

Access Control Lists (ACLs) provided the clearest example of order-dependent configuration. ACLs are lists of rules that routers apply to traffic, permitting or denying packets based on criteria like source address, destination address, or protocol. Crucially, routers process ACL rules sequentially, applying the first matching rule and ignoring all subsequent rules.

Consider an ACL intended to block traffic from one specific host while allowing all other traffic:

access-list 100 deny ip host 192.168.1.50 any

access-list 100 permit ip any any

This works correctly - it denies traffic from 192.168.1.50, then permits everything else. But reverse the order:

access-list 100 permit ip any any

access-list 100 deny ip host 192.168.1.50 any

Now it breaks - the first rule matches all traffic and permits it, so the second rule never executes. The specific deny rule becomes unreachable code, never applied because broader rules above it catch traffic first.

This principle extended to other configurations. Routing protocol metrics and administrative distances created hierarchies where order of preference mattered. Interface configuration sequences sometimes required specific ordering to avoid intermediate invalid states. Understanding these order dependencies required thinking not just about what configurations should exist, but about the sequence in which routers would process or apply them.

Key Lessons: Skills That Transcend Configuration Syntax

While learning specific commands and protocols provided immediate practical value, the deeper lessons transcended particular technologies and became transferable skills applicable throughout networking careers.

1. The OSI Model Transforms from Abstract Theory to Practical Troubleshooting Framework

Before these lab sessions, the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model seemed like academic abstraction - seven layers of networking functionality that existed primarily in textbooks and certification exams. Practical work revealed it as an indispensable troubleshooting framework that guides systematic problem-solving.

When connectivity problems arose, we learned to think and troubleshoot in layers, starting from the bottom and working upward. Physical layer questions came first: Is the cable connected? Are interfaces showing link lights? Is physical connectivity established? Only after confirming physical connectivity did we move to layer 2 (data link), verifying that interfaces were enabled and properly configured at the MAC/switching level.

Layer 3 (network) troubleshooting followed: Are IP addresses correctly configured? Are subnet masks appropriate? Do interfaces fall within expected network ranges? Does IP connectivity exist between adjacent devices? Then layer 3 routing: Are routing tables populated correctly? Do routers know paths to all required networks? Are routing protocols exchanging information successfully?

This layered approach prevented common troubleshooting mistakes like spending hours analyzing routing protocols when the real problem was an unplugged cable, or exhaustively checking IP addressing when the issue was actually routing configuration. The OSI model gave us a mental checklist ensuring systematic coverage of all possible problem domains.

2. Documentation Evolves from Afterthought to Critical Infrastructure Component

As our lab topologies grew more complex, incorporating multiple routers with dozens of interfaces and intricate routing configurations, documentation transformed from optional nicety to absolute necessity. After several hours configuring numerous devices, memory became unreliable - which router had which IP addresses? Which routing protocols ran where? What special configurations existed on particular interfaces?

Effective documentation included multiple components. Topology diagrams showed physical and logical connectivity, making network structure visually apparent. These diagrams needed regular updates as we added connections or modified the topology. IP addressing tables catalogued every interface on every device with its address and subnet mask, preventing address conflicts and making address planning visible. Protocol configuration summaries documented which routing protocols ran on which routers with what specific settings.

Perhaps most valuable were troubleshooting logs - records of problems encountered, symptoms observed, diagnostic steps taken, and solutions applied. These logs created institutional memory, preventing repeated struggles with the same issues. When similar problems arose later, consulting logs often revealed solutions immediately, saving hours of redundant troubleshooting.

In production environments, documentation importance multiplies exponentially. Networks run 24/7 with multiple administrators sharing responsibilities. Good documentation enables knowledge sharing between team members, facilitates training of new staff, supports compliance requirements, and proves invaluable during crisis troubleshooting when stress impairs memory. The documentation habits developed in lab sessions directly translate to professional practice.

3. CLI Mastery Provides Power and Efficiency That GUIs Cannot Match

Many modern network devices offer graphical user interfaces (GUIs) that provide point-and-click configuration alternatives to command-line interfaces. These GUIs appeal to beginners and can simplify certain routine tasks. However, our lab sessions convinced us that true networking expertise requires CLI mastery.

Command-line interfaces enable rapid operation execution. Experienced administrators can configure complex features in seconds through CLI commands that would require navigating multiple GUI screens and dialog boxes. This speed advantage compounds across hundreds or thousands of configuration operations.

CLI facilitates task automation through scripting. Configuration commands can be collected into scripts, enabling repeatable, consistent configuration deployment across multiple devices. GUIs resist automation - clicking buttons and filling forms doesn’t easily translate to automated processes. Organizations managing hundreds or thousands of devices depend on configuration automation, making CLI skills essential.

Remote management through protocols like SSH (Secure Shell) typically operates through CLI, not GUI. When managing devices in distant data centers or troubleshooting problems from home at 3 AM, CLI provides reliable, low-bandwidth access that works even when network conditions prevent GUI operation.

Most fundamentally, CLI promotes deeper understanding. GUI abstractions hide complexity, showing simplified representations that may not accurately reflect underlying device behavior. CLI exposes this complexity, forcing administrators to understand what devices actually do. This understanding becomes crucial during troubleshooting - when things go wrong, you need to know what the device is actually doing, not what a simplified GUI representation suggests it might be doing.

4. Problem-Solving Becomes Systematic Investigation, Not Random Trial and Error

Professional networking distinguishes itself through systematic troubleshooting methodology rather than random experimentation. Each network problem became an investigation requiring structured approach.

Information gathering came first, using show commands to collect data about current system state. What do routing tables show? What are interface statuses? Are routing protocols operating? What does running configuration contain? This phase parallels detective work - gathering evidence before forming theories.

Hypothesis formation followed information gathering. Based on collected evidence, what might be wrong? Is this likely a physical problem, addressing problem, or routing problem? Does the symptom pattern match known problem signatures? Multiple hypotheses often emerged, requiring prioritization based on likelihood and testing difficulty.

Solution testing came next, systematically evaluating hypotheses. Often this meant making temporary changes to test theories - perhaps temporarily modifying routing configuration to see if behavior changed, then reverting changes regardless of outcome. The goal wasn’t just fixing problems but understanding why solutions worked.

Finally came conclusion documentation, recording problem symptoms, investigation steps, and effective solutions. This created organizational knowledge that prevented repeated struggles with similar issues.

This methodology taught patience and discipline. When frustrated by stubborn problems, the temptation arose to randomly change configurations hoping something would work. Systematic methodology prevented this counterproductive approach, ensuring that even when problems persisted, we made steady progress toward understanding and resolution.

5. The Chasm Between “I Understand the Concept” and “I Can Implement It Successfully”

Perhaps the most profound lesson was recognizing the vast distance between intellectual comprehension and practical competence. Reading about OSPF in textbooks provided understanding of concepts - areas, link-state advertisements, designated routers. Configuring OSPF across multiple routers revealed layers of complexity that textbooks simplified or omitted.

Practical implementation exposed subtleties invisible in theory. OSPF neighbor relationships required matching parameters - area IDs, authentication, timers. Getting these wrong prevented adjacency formation, but error messages didn’t always clearly indicate which parameter mismatched. Troubleshooting required systematic verification of every parameter until mismatches revealed themselves.

Performance optimization added another layer. OSPF could be configured to work, but worked well only with appropriate interface cost assignments, proper router ID configuration, and thoughtful area design. Theory mentioned these considerations; practice showed how dramatically they affected real-world operation.

Similar gaps existed across all technologies. Understanding routing in principle differed from efficiently configuring it. Knowing ACL theory differed from debugging why ACLs blocked intended traffic. Theoretical knowledge provided necessary foundation, but practical competence required hands-on struggle with real equipment exhibiting real-world complexity.

Practical Guidance for Aspiring Network Engineers

Based on these intensive lab experiences, several recommendations emerged for anyone beginning their networking journey or working to advance their skills.

1. Embrace Command-Line Interfaces Despite Initial Difficulty

CLI initially appears arcane and user-hostile compared to modern graphical interfaces. This initial difficulty temporarily impairs productivity but yields enormous long-term benefits. Invest time learning fundamental commands until they become reflexive. The efficiency, power, and depth of understanding that CLI mastery provides will multiply throughout your career.

Begin with core commands - interface configuration, routing protocol basics, show commands for verification. Build competence with these before attempting advanced features. Cisco documentation provides excellent command references, and the built-in help system (?) supports exploratory learning.

Practice typing commands manually rather than copying and pasting. Manual typing builds muscle memory, ingraining command structure in ways that copy-paste cannot match. Yes, it’s slower initially, but the long-term skill development justifies the time investment.

2. Maintain Regular Practice to Prevent Skill Atrophy

Networking skills resemble physical skills more than pure knowledge - they require regular exercise to maintain. Without consistent practice, command syntax fades from memory, troubleshooting instincts dull, and theoretical understanding loses its connection to practical application.

If you have lab access, use it consistently rather than cramming before certifications or projects. Regular exposure to equipment builds intuition and confidence that intensive cramming cannot replicate. Even 30 minutes weekly maintaining basic configurations preserves skills far better than sporadic multi-hour sessions separated by weeks of inactivity.

3. Leverage Simulation Tools for Home Practice

Physical equipment access isn’t always practical, but simulation tools enable valuable home practice. Several excellent options exist:

Cisco Packet Tracer provides free access for Cisco Networking Academy participants. While simplified compared to real equipment, it offers excellent learning value for CCNA-level topics. The interface abstracts some complexity, making initial learning gentler, though this also means some real-world behaviors aren’t accurately modeled.

GNS3 (Graphical Network Simulator-3) represents the opposite philosophy - maximum fidelity to real device behavior by running actual router operating systems in virtual machines. GNS3 requires more powerful computers and some technical setup, but it provides experiences much closer to working with physical equipment. Advanced features and behaviors that Packet Tracer simplifies work correctly in GNS3.

EVE-NG (Emulated Virtual Environment - Next Generation) offers professional-grade network emulation, popular in training environments and among networking professionals. It supports wide device variety including multi-vendor environments, enabling experience with Cisco, Juniper, Arista, and other vendors.

Each tool has strengths and appropriate use cases. Beginners might start with Packet Tracer’s gentler learning curve, graduate to GNS3 as skills develop, and potentially use EVE-NG for advanced multi-vendor scenarios or professional development.

4. Create Comprehensive Documentation as Part of Every Practice Session

Develop documentation habits from the beginning rather than treating documentation as optional extra work. Every practice session should produce documentation artifacts - topology diagrams, addressing tables, configuration files, troubleshooting logs.

These documents serve multiple purposes. They provide study materials for later review. They demonstrate growing competence to potential employers through portfolio development. They create personal knowledge bases containing solutions to problems you’ve already solved.

Documentation also develops professional skills directly. Technical writing, diagram creation, structured problem description - these communication skills distinguish exceptional network engineers from merely competent ones. Employers highly value engineers who communicate effectively, documenting their work clearly for colleagues and management.

5. Treat Every Mistake as Educational Opportunity Rather Than Failure

Network configuration involves substantial complexity with countless opportunities for error. Every engineer, regardless of experience level, regularly makes mistakes. The difference between developing engineers and stagnant ones lies in response to mistakes.

When configurations fail, resist frustration and instead cultivate curiosity. Why didn’t this work? What did I misunderstand? What can this failure teach me? Often, mistakes that initially seem most frustrating produce the most valuable learning. You’ll remember lessons from painful troubleshooting far longer than concepts easily mastered.

Maintain troubleshooting logs documenting mistakes and their solutions. These logs become progressively more valuable as they grow, creating personal knowledge bases that prevent repeated errors and accelerate problem resolution when similar issues arise.

6. Build Solid Foundational Understanding Before Pursuing Advanced Topics

Networking knowledge constructs hierarchically - advanced topics depend on firm grasp of fundamentals. Attempting to learn BGP without understanding basic routing produces superficial knowledge that crumbles under scrutiny. Trying to master MPLS without understanding VLANs creates confusion and frustration.

This recommendation requires patience. Foundational topics may seem boring compared to exciting advanced technologies. Subnetting seems tedious; BGP seems fascinating. But engineers who rush past fundamentals inevitably encounter knowledge gaps that impair their understanding of advanced topics, eventually forcing return to basics anyway - but now with added frustration from failed attempts at advanced topics.

Conversely, engineers with rock-solid fundamentals find advanced topics far more approachable. Advanced technologies build on basic principles, and strong foundational understanding provides frameworks for organizing and comprehending new concepts.

Real-World Career Value of Hands-On Laboratory Experience

The investment in practical laboratory experience yields returns throughout networking careers, affecting employment prospects, certification success, professional confidence, and career advancement.

1. Employer Expectations Increasingly Emphasize Practical Competence

Network engineering positions face candidates with similar academic credentials and certification achievements. Practical experience provides powerful differentiation. Candidates who can credibly discuss hands-on troubleshooting experiences, who demonstrate command-line fluency, who understand equipment nuances from direct experience - these candidates stand out dramatically from those with only theoretical knowledge.

During technical interviews, experienced interviewers easily distinguish candidates with genuine hands-on experience from those with only book learning. Questions about troubleshooting methodologies, unexpected device behaviors, or configuration challenges reveal whether candidates have wrestled with real equipment or merely studied about it.

Project work and case studies in interviews become opportunities to showcase practical experience. Candidates can discuss actual topologies built, real problems solved, concrete configuration challenges overcome. This specificity and authenticity resonates far more powerfully than hypothetical discussions of what candidates might do in various scenarios.

2. Certification Examination Success Correlates Strongly with Practical Experience

Cisco certifications (CCNA, CCNP, CCIE) and other networking credentials include practical components that theoretical study alone inadequately prepares candidates for. Simulation questions present scenarios requiring actual configuration and troubleshooting - candidates must demonstrate ability to configure devices and resolve problems, not merely recognize correct answers among multiple choices.

Candidates with extensive hands-on experience approach these simulations naturally, treating them as familiar tasks. Their muscle memory types commands automatically, their troubleshooting instincts engage naturally, and their practical knowledge fills gaps that theory left unclear.

Conversely, candidates relying primarily on theoretical study struggle with simulations despite perhaps excelling at multiple-choice questions. Knowing conceptually what should be configured differs from fluently executing configurations under time pressure. Understanding troubleshooting methodology in principle differs from quickly diagnosing and resolving actual problems.

Beyond simulations, practical experience improves performance on all question types. Experience provides context that makes theoretical concepts more concrete and memorable. Real-world examples illustrate abstract principles, making recall easier during examinations.

3. Professional Confidence Emerges from Demonstrated Competence

Perhaps the most personally valuable outcome of hands-on experience is genuine professional confidence. Engineers who have successfully configured routers, built working topologies, and resolved complex problems possess internalized confidence that no amount of theoretical study provides.

This confidence affects job performance in subtle but significant ways. Confident engineers approach new challenges with expectation of success rather than fear of failure. They troubleshoot methodically rather than panicking when problems arise. They communicate more effectively with colleagues and management because they trust their own competence.

Imposter syndrome - feeling like fraud who will soon be exposed as incompetent - affects many technical professionals, but hands-on experience provides powerful antidote. When you’ve actually done the work, configured the equipment, solved the problems, you possess concrete evidence of competence that feelings of inadequacy cannot override.

4. Professional Networking Creates Career-Long Value

Laboratory sessions provide more than technical skills - they create professional networks with fellow students sharing similar interests and career goals. These connections often yield career value exceeding the technical knowledge gained.

Classmates become colleagues, either directly (working at the same companies) or indirectly (working in related industries or positions where collaboration opportunities arise). They become professional references who can authentically vouch for your technical competence and work habits. They become information sources providing insights into their companies, industries, or specializations.

These professional relationships develop naturally through shared struggle. Working together to troubleshoot stubborn configurations, celebrating successful implementations, commiserating over frustrating problems - these shared experiences build relationships that pure networking events rarely replicate.

Maintain these connections through professional networking platforms, occasional communication, and mutual assistance. The network engineer you help troubleshoot a problem today may refer you for a position at their company tomorrow, or may become the colleague who helps you solve a critical problem years from now.

Advanced Concepts and Their Practical Implications

Beyond basic router configuration and simple routing, our lab sessions explored several advanced topics that provided glimpses into the sophistication and complexity of production networks.

VLANs and Inter-VLAN Routing: Logical Network Segmentation

Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs) demonstrated one of networking’s most powerful concepts - logical separation overlaid on physical infrastructure. A single physical switch could be logically segmented into multiple isolated networks, as if multiple physical switches existed.

We configured VLANs on switches, assigning different ports to different VLANs:

Switch(config)# vlan 10

Switch(config-vlan)# name Engineering

Switch(config-vlan)# exit

Switch(config)# vlan 20

Switch(config-vlan)# name Sales

Switch(config-vlan)# exit

Switch(config)# interface FastEthernet0/1

Switch(config-if)# switchport mode access

Switch(config-if)# switchport access vlan 10

Devices in VLAN 10 could communicate with each other but remained isolated from VLAN 20, despite all devices connecting to the same physical switch. This segmentation provided security (preventing unauthorized access between departments), performance (reducing broadcast domains), and management flexibility (logical reorganization without physical recabling).

Trunk ports enabled VLAN information to traverse multiple switches, extending VLANs across physical infrastructure:

Switch(config)# interface GigabitEthernet0/1

Switch(config-if)# switchport mode trunk

Switch(config-if)# switchport trunk allowed vlan 10,20,30

A single trunk connection could carry traffic for multiple VLANs, with special tags identifying which VLAN each frame belonged to. This multiplexing dramatically reduced cabling requirements in multi-switch environments.

Inter-VLAN routing proved particularly interesting. Devices in different VLANs, by design, cannot directly communicate - they’re in isolated layer 2 broadcast domains. For cross-VLAN communication, traffic must traverse a router operating at layer 3.

We implemented router-on-a-stick configurations where a single router interface handled inter-VLAN routing for multiple VLANs through sub-interfaces:

Router(config)# interface FastEthernet0/0

Router(config-if)# no shutdown

Router(config-if)# exit

Router(config)# interface FastEthernet0/0.10

Router(config-subif)# encapsulation dot1Q 10

Router(config-subif)# ip address 192.168.10.1 255.255.255.0

Router(config-subif)# exit

Router(config)# interface FastEthernet0/0.20

Router(config-subif)# encapsulation dot1Q 20

Router(config-subif)# ip address 192.168.20.1 255.255.255.0

This configuration created logical sub-interfaces on a single physical interface, each associated with different VLAN and serving as gateway for that VLAN’s devices. The elegance of this solution - extensive VLAN segmentation with minimal physical infrastructure - illustrated networking’s power to create logical functionality independent of physical constraints.

Access Control Lists: Network Security Through Traffic Filtering

Access Control Lists (ACLs) introduced security concepts, demonstrating how routers function not just as traffic forwarders but as selective gatekeepers controlling which traffic flows where.

Standard ACLs provided basic filtering based on source IP addresses:

Router(config)# access-list 10 deny 192.168.1.50

Router(config)# access-list 10 permit any

Router(config)# interface FastEthernet0/1

Router(config-if)# ip access-group 10 out

This configuration blocked traffic from host 192.168.1.50 while permitting all other traffic. Simple, but effective for basic security requirements.

Extended ACLs offered sophisticated control based on multiple packet characteristics - source address, destination address, protocol, port numbers:

Router(config)# access-list 100 deny tcp 192.168.1.0 0.0.0.255 192.168.2.0 0.0.0.255 eq 23

Router(config)# access-list 100 permit ip any any

Router(config)# interface FastEthernet0/0

Router(config-if)# ip access-group 100 in

This blocked Telnet traffic (port 23) from the 192.168.1.0/24 network to 192.168.2.0/24 network while allowing all other traffic. Such granular control enables implementing detailed security policies.

ACL configuration reinforced the critical importance of rule ordering and placement. Rules must be ordered from most specific to most general, because routers apply the first matching rule and ignore subsequent rules. ACL placement - where in the network topology they’re applied - dramatically affects their effectiveness and impact on network performance.

Wildcard masks initially confused many students. Unlike subnet masks (which have contiguous ones followed by contiguous zeros), wildcard masks use zero to indicate bits that must match and one to indicate bits that can vary. The wildcard mask 0.0.0.255 means “first three octets must match exactly, fourth octet can be anything” - matching an entire /24 network. This inverted logic required practice to internalize.

Network Address Translation: Bridging Private and Public Addressing

Network Address Translation (NAT) solved a critical problem - IPv4 address exhaustion. With only about 4 billion possible IPv4 addresses and far more networked devices globally, NAT enables multiple devices sharing single public IP addresses.

We implemented basic NAT configurations demonstrating how internal private addresses (RFC 1918 addresses like 192.168.x.x, 10.x.x.x, 172.16-31.x.x) translate to public addresses for Internet communication:

Router(config)# access-list 1 permit 192.168.1.0 0.0.0.255

Router(config)# ip nat inside source list 1 interface Serial0/0 overload

Router(config)# interface FastEthernet0/0

Router(config-if)# ip nat inside

Router(config-if)# exit

Router(config)# interface Serial0/0

Router(config-if)# ip nat outside

This configuration enabled Port Address Translation (PAT), also called NAT overload, where multiple internal devices share a single public IP address through port number manipulation. This is how home routers typically operate, allowing entire households to share single public IP addresses from ISPs.

Understanding NAT provided insights into why certain applications struggle with NAT (especially peer-to-peer applications or servers behind NAT), why NAT complicates end-to-end connectivity (breaking the Internet’s original design philosophy), and why IPv6 adoption matters (IPv6’s vast address space eliminates NAT necessity for most purposes).

Common Mistakes: Learning from Errors

Documenting common mistakes and their prevention strategies provides practical value for students beginning similar journeys. These aren’t just hypothetical problems - they’re errors I actually made and learned from painfully.

Mistake 1: Configuring Without Saving, Then Losing Everything

Cisco routers maintain two separate configuration stores: running-config stored in RAM (active but volatile), and startup-config stored in NVRAM (persistent but not automatically updated). This separation provides useful rollback capability but creates trap for unwary beginners.

I spent over an hour carefully configuring a router - setting hostname, configuring interfaces, implementing routing protocol, creating access lists. Feeling satisfied with my work, I prepared to move to the next device. Then the instructor performed an unexpected power cycle. When the router rebooted, everything was gone - back to default configuration.

The lesson was stark: running-config disappears on reboot unless explicitly saved to startup-config. The command is simple:

Router# copy running-config startup-config

Or more concisely (but less clearly):

Router# write memory

After this painful lesson, saving configuration became reflexive habit after every significant change. In production environments, this practice prevents catastrophic losses during power failures or equipment problems.

Mistake 2: Meticulous Configuration Undermined by Forgotten “no shutdown”

After carefully configuring interface IP addressing, verifying every digit of addresses and subnet masks, consulting topology diagrams to ensure correctness, I tested connectivity. Nothing worked. Ping failed, routing tables showed nothing about this network, the interface appeared non-functional.

Twenty minutes of troubleshooting followed - rechecking addresses, verifying cables, examining routing protocol configurations. Finally, checking interface status revealed: “FastEthernet0/0 is administratively down, line protocol is down.”

The interface was shutdown - Cisco’s default state. Despite thorough configuration of every aspect of the interface, I’d forgotten the final crucial command:

Router(config-if)# no shutdown

This simple command administratively enables the interface, allowing it to actually function. Without it, all other configuration is irrelevant.

This mistake taught the value of systematic post-configuration verification using show commands rather than assuming configurations work correctly.

Mistake 3: Asymmetric Troubleshooting - Checking Only One Half of Problem

When connection between Router A and Router B failed, I naturally began troubleshooting on Router A. I methodically verified its configuration - IP address correct, subnet mask appropriate, interface enabled, routing information present. Everything looked perfect.

After exhausting troubleshooting on Router A, frustration mounting, I finally checked Router B. Immediately obvious - Router B had wrong subnet mask. Despite Router A’s perfect configuration, the connection couldn’t work because Router B was misconfigured.

The lesson: network problems require checking both ends of connections. Never assume one side is correct and focus exclusively on the other. Systematic troubleshooting verifies all components, even when confident about their correctness.

Mistake 4: Sophisticated Configuration Debugging When The Problem Was Unplugged Cable

Faced with routing protocol that wouldn’t form neighbor relationships despite seemingly correct configuration, I dove into sophisticated troubleshooting. I examined authentication settings, verified area configurations, checked timer values, analyzed debug output, consulted protocol RFCs to understand adjacency formation requirements.

After an hour of complex protocol analysis, a classmate walked by and asked, “Is that cable plugged in all the way?” I pushed the cable - it clicked fully into place. Immediately, the protocol adjacency formed.

This humbling experience taught networking’s fundamental principle: always verify physical layer first. Start with obvious physical problems (cables, ports, power) before investigating sophisticated configuration issues. Physical problems often manifest as logical symptoms, but no amount of configuration expertise fixes physical disconnections.

Mistake 5: Shotgun Troubleshooting - Changing Everything Hoping Something Works

Confronted with stubborn connectivity problem, frustration drove me to random configuration changes. I modified routing protocol settings, changed interface addresses, adjusted administrative distances, altered ACLs - making multiple changes simultaneously, desperately hoping something would fix the issue.

This approach transformed a single problem into multiple problems. Now I couldn’t determine which changes had positive effects, negative effects, or no effects. Even when connectivity eventually worked, I didn’t understand why, preventing me from learning from the experience or solving similar future problems.

The instructor stopped me, had me reload the router back to last known good configuration, and enforced discipline: make one change at a time, test after each change, document results. This systematic approach felt slower initially but consistently proved faster than random experimentation.

This lesson extends beyond networking - systematic problem-solving beats frustrated randomization in every domain.

Certification Preparation: From Lab to Credentials

The hands-on laboratory experience directly prepares students for industry certifications that validate networking competence and significantly impact career prospects.

CCNA: Foundational Certification Built on These Fundamentals

The Cisco Certified Network Associate (CCNA) certification represents entry-level professional competence in Cisco networking technologies. Everything covered in our lab sessions - router configuration, switching fundamentals, IP addressing, routing protocols, basic security - constitutes core CCNA content.

CCNA examinations include multiple question types, but simulation questions particularly benefit from hands-on experience. These simulations present network scenarios with specific problems or requirements, then provide access to device CLIs where candidates must diagnose problems or implement configurations to meet requirements.

Candidates with extensive hands-on practice approach these simulations naturally. They’re comfortable with CLI navigation, familiar with command syntax, experienced with troubleshooting methodologies. They work efficiently under time pressure because their skills are ingrained through practice, not recently memorized.

Theory-focused candidates often struggle with simulations despite perhaps answering multiple-choice questions correctly. Knowing conceptually how to configure OSPF differs from actually typing correct commands under pressure, troubleshooting when adjacencies don’t form, and verifying operation within time constraints.

Beyond simulations, practical experience improves performance on all question types. Real-world examples provide memory anchors making theoretical concepts more concrete and easier to recall during examinations.

CCNP and Beyond: Building on Solid Foundations

Advanced certifications like CCNP (Cisco Certified Network Professional) and ultimately CCIE (Cisco Certified Internetwork Expert) build on the same foundational skills developed in basic lab sessions.

CCNP examination difficulty increases substantially, covering more complex scenarios, advanced protocol features, and sophisticated troubleshooting. However, the fundamental skills remain constant - CLI competence, systematic troubleshooting methodology, deep protocol understanding. Engineers with solid hands-on foundations find advanced certifications challenging but approachable.

CCIE laboratory examinations represent networking certification’s pinnacle, requiring candidates to demonstrate expert-level competence through eight-hour hands-on examinations configuring and troubleshooting complex multi-vendor networks. These grueling tests are passable only with extensive practical experience - no amount of theoretical study alone suffices.

The laboratory skills developed in basic training provide foundations that support entire certification progression paths. Early investment in hands-on competence yields returns throughout careers.

CompTIA Network+ and Vendor-Neutral Certifications

While our lab work focused on Cisco equipment, the underlying networking principles apply universally. CompTIA Network+, a vendor-neutral certification, covers the same fundamental concepts - OSI model, IP addressing, routing, switching, network security.

Experience configuring Cisco equipment translates to understanding networking generally. While command syntax varies between vendors, the concepts remain constant. Engineers who understand routing on Cisco routers grasp routing on Juniper, Arista, or any other vendor’s equipment - it’s the same underlying protocols and principles with different implementation details.

This universality makes hands-on experience with any major vendor’s equipment valuable preparation for vendor-neutral certifications and for career flexibility across different network environments.

Future Directions: Continuing the Learning Journey

These initial laboratory sessions represent beginning, not culmination, of networking education. Multiple paths forward exist, each offering opportunities for skill development and career advancement.

1. Home Laboratory Setup for Continuous Practice

Maintaining regular practice outside formal laboratory environments requires home lab setup. Several approaches exist with varying cost and complexity trade-offs.

Physical equipment can be acquired surprisingly affordably through secondary markets. Older Cisco equipment (routers, switches from previous generations) often sells for prices ranging from insignificant to modest. While not current production models, these devices run authentic Cisco IOS and provide genuine hands-on experience. EBay, equipment recyclers, and IT asset disposition companies represent potential sources.

Physical equipment advantages include authenticity - it’s actual hardware running actual software, identical to what professionals use. Disadvantages include power consumption, heat generation, noise (fans!), and space requirements. Physical labs work well for dedicated learners with appropriate space and tolerance for ongoing equipment operation.

Virtual laboratories using GNS3 or EVE-NG offer powerful alternatives. These simulators run actual router operating systems in virtual machines, providing near-authentic experience without physical equipment requirements. Modern computers easily handle multiple virtual routers, enabling complex topology practice.

Virtual lab advantages include flexibility (easily modify topologies), silence (no fan noise), and power efficiency. Disadvantages include initial setup complexity and powerful computer requirements for large topologies. Virtual labs excel for students lacking dedicated space for physical equipment or requiring flexibility to practice anywhere.

Hybrid approaches combining physical and virtual equipment offer interesting possibilities - perhaps physical switches for layer 2 practice combined with virtual routers for layer 3 and routing protocol work.

2. CCNA Certification Pursuit

With solid practical foundations, pursuing CCNA certification represents natural progression. This certification validates competence, enhances resumes, often increases earning potential, and provides structured learning path through comprehensive networking topics.

Modern CCNA (updated February 2020) covers extensive content: networking fundamentals, network access, IP connectivity, IP services, security fundamentals, and automation/programmability basics. The breadth is substantial, requiring dedicated study beyond basic laboratory work.

Certification preparation should combine multiple approaches: continued hands-on lab practice, theoretical study through official cert guides or video courses, practice examinations to familiarize with question formats and identify knowledge gaps, and joining study groups or online communities for support and knowledge sharing.

The certification journey provides valuable structure to self-directed learning and results in credential recognized industry-wide.

3. Network Automation and Programmability

Modern networking increasingly incorporates automation and programmability. While traditional CLI-based manual configuration continues, large networks increasingly leverage automation tools and programming for configuration management, monitoring, and orchestration.

Python programming language has emerged as networking automation standard. Learning Python enables creating scripts that configure multiple devices simultaneously, extract information from devices for analysis, monitor network health, and automate repetitive tasks.

Ansible, a popular automation platform, enables network configuration management through playbooks describing desired network state. Engineers write playbooks defining configurations, then Ansible applies those configurations across device fleets, ensuring consistency and reducing manual configuration errors.

REST APIs (Representational State Transfer Application Programming Interfaces) provide programmatic interfaces to network devices, enabling software to query status and modify configurations without traditional CLI interaction.

These automation skills build on solid networking fundamentals - you must understand networking deeply to automate it effectively. However, automation dramatically amplifies individual engineer capabilities, enabling management of networks orders of magnitude larger than manual configuration permits.

4. Specialization Areas

Networking offers numerous specialization paths, each representing distinct career tracks with specific skill requirements:

Network Security focuses on protecting networks from threats through firewalls, intrusion prevention systems, VPNs, and security policy implementation. This specialization combines networking knowledge with security expertise.

Wireless Networking covers Wi-Fi design, deployment, and management. Wireless brings unique challenges around RF propagation, interference, roaming, and density support for high device counts.

Data Center Networking addresses specialized requirements of data center environments - very high bandwidth, low latency, high reliability, and massive scale. Technologies like VXLAN, spine-leaf architectures, and data center interconnect create distinct expertise area.

Service Provider Networking involves ISP and carrier networks, introducing technologies like MPLS, BGP at scale, and metro Ethernet. These networks operate at scales far beyond enterprise environments with corresponding complexity.

Software-Defined Networking (SDN) represents emerging paradigm separating control plane from data plane, enabling centralized network control through software controllers. SDN promises increased flexibility and automation.

Each specialization builds on networking fundamentals while developing focused expertise in specific domain. Initial broad networking knowledge positions engineers to explore specializations and identify areas matching their interests and aptitudes.

5. Perpetual Learning in Evolving Field

Technology evolution never stops. Software-Defined WAN (SD-WAN) transforms branch connectivity. Intent-Based Networking promises networks that automatically configure themselves based on policy intentions. Cloud networking introduces new architectures and challenges. IPv6 deployment accelerates. Network Function Virtualization (NFV) replaces specialized hardware with virtual appliances.

Successful networking careers require commitment to continuous learning. Following industry publications, participating in professional communities, attending conferences or webinars, experimenting with emerging technologies - these activities maintain relevance as technology evolves.

The fundamentals learned in laboratory sessions remain valuable indefinitely. While specific protocols or technologies may evolve, core principles of packet forwarding, protocol design, and systematic troubleshooting endure. Strong foundations enable learning new technologies efficiently as they emerge.

Conclusion: Transformation Through Practice

These hands-on networking laboratory sessions fundamentally transformed my understanding of networking from theoretical concepts to practical competencies. The journey from initial uncertainty when first connecting to router consoles through eventually configuring complex multi-router topologies represents profound skill development.

The photographs documenting our lab work show racks of equipment, tangles of colorful cables, and blinking status LEDs. What they cannot capture is the frustration when carefully crafted configurations inexplicably failed, the satisfaction when stubborn problems finally yielded to systematic troubleshooting, the excitement of those “aha!” moments when concepts suddenly crystallized from confusion to clarity, the camaraderie among students struggling together through shared challenges, and the growing confidence that emerged from repeatedly succeeding at increasingly complex tasks.

For anyone studying networking or contemplating entering this field, I cannot overemphasize the value of hands-on laboratory experience. Reading textbooks provides essential theoretical foundations. Watching demonstration videos offers helpful examples. But nothing replaces the experience of working directly with equipment, making real mistakes with real consequences, encountering unexpected problems that textbooks never mentioned, and developing troubleshooting instincts through repeated practice.

The path from “I’ve read about networking concepts” to “I can configure and troubleshoot real networks” runs directly through laboratories like these. It’s challenging work that occasionally frustrates, but the skills developed prove invaluable throughout entire careers. Every expert network engineer remembers their early laboratory experiences - those formative sessions where theoretical knowledge transformed into practical competence.

To anyone beginning their networking journey: Embrace every laboratory opportunity. Don’t just follow instructions mechanically - understand why each step matters. Ask questions fearlessly, even when they seem basic - no question is too simple if it deepens your understanding. Experiment boldly with configurations in safe laboratory environments - break things deliberately to learn how to fix them. Document your work meticulously - future you will thank present you for those notes. Most importantly, persist through frustrations - every struggle builds skills and every mistake teaches lessons.

Remember that every networking expert began exactly where you are now - as a beginner uncertain about basic concepts, making common mistakes, gradually building competence through practice and persistence. The difference between beginners and experts isn’t innate talent - it’s accumulated experience gained through dedicated practice over time.

The skills developed in these laboratory sessions form foundations supporting entire networking careers. Whether you pursue certifications, specialize in particular networking domains, or move into emerging areas like automation and SDN, the core competencies developed through hands-on practice remain relevant and valuable.

Networking offers fascinating, challenging, and rewarding careers for those willing to invest in developing practical skills. These laboratory sessions represent just the beginning of that journey - an essential first step toward expertise that will serve you throughout your professional life.